Why History May Not Be Kind To William Crowther

by Bonnie Mary Liston

Warning: This article has graphic themes and discusses body mutilation. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples should be aware that this article contains names of people who have passed away.

William Lodewyk Crowther was the 14th premier of Tasmania. Crowther was a man of science, a doctor and surgeon as well as a keen amateur naturalist. As a child walking to and from school he developed an interest in the wildlife of Tasmania. He pursued this passion by trapping birds and animals, killing them and collecting their skins.

When he travelled to London to continue his education he sold his collection, by then consisting of over 493 skins and a pair of live Tasmanian Devils, to the Earl of Derby for a tidy price that was enough to pay for his training at St Thomas’s Hospital and allow him an extra year of study in Paris. He returned to Tasmania to work in his father’s practice. He had 11 children and many business interests including sawmills, guano, sealing and whaling, not to mention a political career.

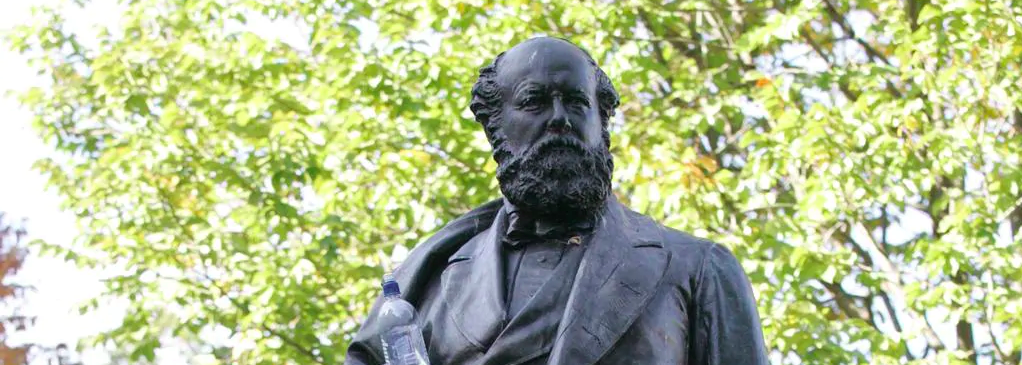

When he died in 1885 he was described as “impulsive, hard and dour” but had enough fans that a statue was erected on him in Franklin Square in 1889, funded by public subscription. That statue stands to this day, despite growing more controversial over time. Many people object to such a public monument aggrandising Crowther, particularly one that makes no mention of his role in the mutilation of William Lanne.

William Lanne, also known as King Billy, was a Tasmanian Aboriginal man, the youngest child in the last family sent to Wybalenna, the Aboriginal containment camp on Flinders Island, and one of only 47 survivors who escaped it. He grew up to be a sailor, by all accounts cheerful and popular. He was also a great advocate of the Indigenous community at Oyster Bay.

Despite being nearly 30 years her junior, he married Truganini, becoming her third husband (you go girl). The King Billy Pine or Athrotaxis selaginoides, is named for him. When he died in 1869 it was believed he was the last “full-blooded’’ Tasmanian Aborinal man in the world and a gruesome battle erupted between the Royal College of Surgeons of England and the Royal Society of Tasmania over his corpse.

Crowther, on behalf on the College of Surgeons, broke into the morgue where Lanne’s body lay and decapitated him, sliced open his face and peeled off the skin, removing his skull and replacing it with the skull of a white man, stolen from another corpse in the morgue. He then stitched him back up, attempting to cover his crime. The Tasmanian Royal Society retaliated by removing William’s hands and feet for their collection. He was buried in this mutilated state – his funeral was large and well attended by friends and community. A police guard was left over his grave to prevent further desecration but the next morning they found the grave dug up and surrounded by blood.

The imposter skull had been discarded, lying next to the grave, suggesting the culprit knew it was not William’s. However when Crowther returned to the hospital where he had stashed the body he discovered all that remained was “masses of fat and blood.” William had been deboned and his skeleton stolen, presumably by the Tasmanian Royal Society though it was never recovered. The grotesque affair became a major scandal at the time, and Crowther lost his position as honorary medical officer at Hobart General Hospital as a result. However white men never let anything as trifling as justice get in their way and Crowther would go on to win election to Premiership, get libraries named after him and fancy statues erected in public places. Crowther never really escaped his actions within his lifetime – even 15 years after Lanne’s death Crowther was being accosted on the street about the incident.

However hundreds of years later many people know nothing about him or King Billy and all his statue perpetuates is “the memory of long and zealous political and professional service in this colony,” to quote its inscription. All around the world people have to grapple with the contentious issue of what to do with ahistorical monuments erected by people in power. In America there are those outraged by taking down Confederate statues, even in states that never actually succeeded. In the case of Crowther’s statue, Mayor Anna Reynolds has proposed an alternate solution. The Hobart City Council invited artists to submit proposals for temporary arts works that respond to the Crowther Stature – particularly those addressing “Crowther’s actions, Lanne’s story as an Aboriginal leader, the politics of 1860s Hobart, current views on Crowther, or the validity of bronze statues in modern cities.”

Four artworks have been chosen, with priority given to Tasmanian Aboriginal artists, and each work will be displayed alongside the statue at Franklin Square for approximately two months. Mayor Reynolds hopes the project will “provoke conversation, engagement and reflection in the community,” and says that the community’s response to the works will inform the Council’s permanent response to the statue, as yet undecided. Crowther’s statue is far from the only monument in Hobart that uncritically valorizes problematic historical figures. This project may set an important precedent for how we can contextualise and expand our understanding of our own past.

Find out more about the project here.