The Fishy Story Of The Salmon Ponds

by Amanda Double

It’s been a long time since I’ve visited the Salmon Ponds at Plenty, near New Norfolk – the oldest trout hatchery in the Southern Hemisphere. But now I’m here with a friend on a cold day, I’m reminded of the fascinating story of their origins.

The colonists, so far from all they were used to, wanted to be able to fish for salmon in their new home. At first it seemed impossible, their dream to transport live salmon and trout fry or fertilised eggs (ova) across the ocean to Tasmania, and early attempts did indeed fail. In 1857 the Tasmanian Parliament announced an impressive reward of five hundred pounds for “the introduction of live salmon”, and in 1861 a Salmon Commission was formed.

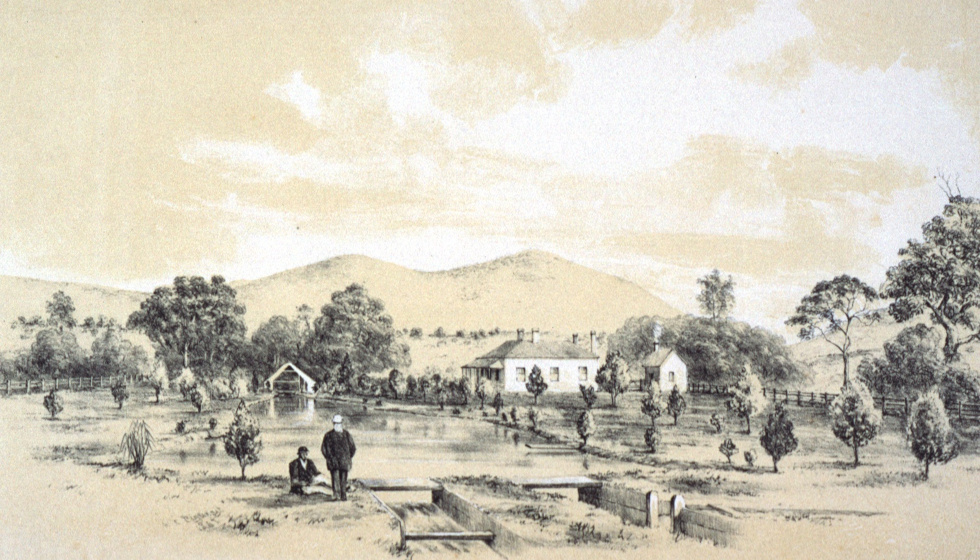

The Commissioners chose Plenty, some 50 km north-west of Hobart, as the most suitable place to construct the Salmon Ponds, with the Plenty River (a tributary of the Derwent) fed by cold, clear water and offering young fish a clear passage to the sea. The Ponds were built in 1862, on property leased from Mr Robert Read of “Redlands” (and eventually bequeathed by his son George to the Crown), and were based on the plans of famous salmon ponds on the River Tay in Scotland. However, Jean Walker in her excellent history Origins of the Tasmanian trout: an account of the Salmon Ponds and the first introduction of salmon and trout to Tasmania in 1864 (published by the Inland Fisheries Commission in 1988) details how costly attempts to transport salmon ova continued to fail until January 1864, when a special icehouse was built on board the Norfolk square-rigged wooden ship to transport them. Pastoralist James Youl moved heaven and earth to obtain suitable salmon ova, and at the last minute trout ova were added as well. Walker records how the ova were packed in the icehouse in pine boxes perforated with holes at the top, bottom and sides to allow melting ice to flow in and percolate through the moss and ova inside: “A couple of handfuls of charcoal were spread over the bottom of each box, then a layer of broken ice, after this a bed, or nest, of wet moss was carefully made and well drenched with water. The ova were then very gently poured from a bottle which was kept filled with water. The box was then filled up with moss and pure water poured upon it until it streamed out from all the holes. Another layer of finely pulverised ice was then spread all over the top of the moss and the lid was then firmly screwed down.”

Approximately 100,000 Atlantic salmon and 3,000 brown trout ova were included, in 181 boxes, with William Ramsbottom accompanying as custodian. Ramsbottom apparently later confessed to a friend that every time there was rough weather on board he told himself nervously, “there goes another thousand of them!” The Norfolk arrived in Melbourne first and left 11 boxes of the ova with the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria, while the remainder were carefully transferred to the Victoria, the Victorian Navy’s warship, for transportation to Hobart. The ship arrived in the Derwent on 20 April 1864. Crowds had gathered to welcome her, on shore and in small boats, with The Mercury reporting the following day that: “…on her arrival the vessels in harbor dressed in all their gayest colours. No salute was fired, but the Kangaroo steamer, which happened to be crossing at the time, fired three guns, and dipped her ensign to the Victoria; the Crishna barque also dipped her ensign as the Victoria came up.”

The precious cargo finally arrived at the Salmon Ponds on 22 April 1864 by various means of transport, 91 days after being placed on board the Norfolk in England – with an estimated 30,000 ova miraculously still alive, about 300 of which were trout. According to The Mercury, after the initial trepidation, “As box after box was opened, exclamations of delight broke from Mr. Ramsbottom, and…it was become almost a matter of certainty that the painstaking patient labours so scientifically directed, had achieved another and a great triumph.”

By 8 June, 300 trout and several thousand salmon had successfully hatched, to begin the new enterprise in the southern hemisphere. Somewhat ironically, however, the Atlantic salmon venture failed, as once released the salmon disappeared, never returning to the Derwent River as expected. It was the non-migratory trout, added to the ship only at the last minute, which were to prove so successful that they were to eventually help establish trout hatcheries throughout Australia and New Zealand.

The Salmon Ponds were a great success right from the start. One early tourist wrote a vivid description published in the Sydney Morning Herald of 14 February 1867 as A trip to the Salmon Ponds at the River Plenty: “A holiday afforded me the leisure for a visit to the salmon ponds… The vale of Plenty, where the ponds are situated, is very beautiful and picturesque. A stream of water, diverted from the river for irrigation, flows through the plains, and gives fertility to the meadows and an extensive hop ground. Mr. Ramsbottom’s house and grounds are all new, and the wonder is that so much could have been done in so brief a space with the funds at command. But the vigour and freshness of the vegetation are not to be wondered at when you look at the several streams flowing through the plantation. Considerable taste has been evinced to make the canals, ponds, and shrubberies harmonise. The first object of attraction, apart from the beauties of the landscape, was a pond containing a number of large brown trout, weighing from one to two pounds each. The clearness of the water in this artificially constructed pond, with a gravel bed, and a good stream flowing through it, enabled us to see the fish perfectly.”

Today, several different trout species and hybrids are on display – Rainbow, Brook and Tiger Trout along with the Brown Trout, as well as some unusual-looking Albino Rainbow Trout. And a few Atlantic Salmon, to justify the Salmon Ponds name. We feed them all pellets obtained from the $2 coin dispensers (my friend swears that years ago, packets of Twisties were accepted as fish food here!). Some don’t seem very hungry, although others leap out of the water momentarily as they gobble up the pellets. One takes me so much by surprise that I shriek as I’m splashed – and then look around furtively to see if everyone is looking at me.

We amble along the river track, before visiting the historic Hatchery, the Museum of Trout Fishing (housed in the cottage built for the first Superintendent), and the Tasmanian Angling Hall of Fame, complete with Honour Board. I note with interest that the 2023 inductee was Sheryl Thompson, the first female awarded this honour, who paved the way for female participation in fishing in Tasmania.

Just before we head to the cafe to indulge in one of their signature pancakes, we are gifted with one final, delightful surprise: a little platypus bobs up from the water in one of the ponds, resting on the surface briefly but repeatedly as if to say hello. Although usually shy and wary, platypus are apparently regular visitors here at certain times of the year. It’s the perfect finale to our stroll around the Salmon Ponds and Heritage Gardens.