The First Tasmanian to Set Foot on Antarctica

by Hobart Magazine

The end of the 19th century heralded the beginning of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. This was an era marked by intensive scientific and geographical exploration in the Antarctic region. Hobart became one of the few cities that served as a hub for Antarctic explorers, due to its geographical proximity to the frozen continent, and its deepwater estuary which enabled explorers to use its harbour.

Picture the Hobart waterfront all those years ago. Towering ships moored in the harbour, and adventurers filling the streets, eagerly awaiting the journey of a lifetime. Today, Hobart’s profound ties with Antarctica are ingrained in the city’s history and culture. From hosting the annual Australian Antarctic Festival, (this year from 22-25 August), to fostering scientific research through institutions like IMAS and CSIRO, Hobart never ceased being a pivotal base for Antarctic discovery.

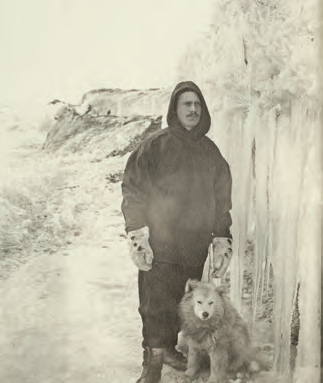

Throughout the city, there are memorials that remind us of this storied legacy. Among these stands the bronze statue titled Self portrait, Louis and Joe at Constitution Dock. Perhaps familiar to many who have passed by, or even posed for photos with it, the statue commemorates Tasmanian Antarctic explorer Louis Bernacchi and his loyal Siberian husky, Joe. Bernacchi was the first Tasmanian to set foot on continental Antarctica and the first Australian to work and winter in Antarctica.

Louis Bernacchi, born in 1876 to Italian parents in Belgium, migrated with his family to Tasmania at the age of seven. They settled on Maria Island, where his father, Angelo Bernacchi, established a vineyard. It was here, amidst the island’s serene remoteness, that Louis’s curiosity and passion for nature grew.

Bernacchi was educated at Hutchins in Hobart, then at 19 he went to the Melbourne Observatory to learn about meteorology and terrestrial magnetism (think Earth’s magnetic field). It was during this time that his fascination with Antarctic exploration was sparked, given its relevance to his studies.

In 1898, at the age of 22, Louis finally got to venture to the continent. His training made him suitable for the role of physicist, so he joined the privately financed Southern Cross Expedition, led by Carsten Borchgrevink, comprising 31 men and 90 sled dogs (the first dogs to be taken to Antarctica). It was the first British venture of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, before the more widely known Shackleton and Mawson expeditions. This truly was a voyage into the icy unknown.

This expedition was marked by many historic ‘firsts’. Only 10 men, Bernacchi among them, stayed in the continent. They were the first to brave an entire winter on the Antarctic mainland, they pioneered the use of dogs and sledges for Antarctic travel, they erected the first buildings in Antarctica (which still stand today at Cape Adare), and they achieved a record for farthest south travelled (later surpassed on Bernacchi’s second voyage). Tragically, the expedition also witnessed Antarctica’s first burial, that of Nicolai Hanson, who succumbed to illness. His death caused great sadness amongst the men.

Bernacchi played a crucial role overseeing meteorological observations and photography. These efforts were pivotal in understanding geomagnetic data in Antarctica. His detailed account of the expedition, titled To the South Polar Regions was published in 1900 and featured his photos, which are the first comprehensive visual record of Antarctica on land. Later, his granddaughter Janet Crawford edited a version of his diaries from the expedition under the title That First Antarctic Winter.

These two texts shine a light on what everyday life was like. They reveal poor leadership, conflict amongst the crew, and a generally uncomfortable atmosphere, though Bernacchi was known to be a peacemaker and to have kept a cool head. Because the expedition was privately financed and not an official British venture, it garnered little public attention upon its conclusion. Nonetheless their legacy lives on in Bernacchi’s words and photos, the crew’s findings, and the monuments they left behind.

In the first year of the expedition, a puppy named Joe was born and given to Bernacchi. They developed a close bond and kept each other company. After Joe had been trained, Bernacchi put him to work, and upon returning home, he brought Joe with him. He would then bring the husky on his second Antarctic expedition.

This was the Discovery Expedition, led by Robert Falcon Scott, spanning from 1901 to 1904. Unlike Bernacchi’s first Antarctic venture, this garnered widespread attention and acclaim as it was the first official British voyage of this era. It boasted a significantly larger budget, more resources, and a larger crew (including Ernest Shackleton, who would go on to become one of the most important figures in Antarctic history). It was a more epic journey by all accounts, and worth further reading.

Bernacchi was the only person onboard who had been to Antarctica before, making him an essential part of the team. He would have been sharing his tales and knowledge as the ship made its way to colder waters. Back in the Antarctic, he continued his research among several other scientists.

The crew discovered the continent’s only snow-free valley and its longest river, significant penguin colonies, and the Polar Plateau where the South Pole is situated. They unearthed fossils, identified new marine species, amassed thousands of geological and biological specimens, and calculated the positions and heights of more than 200 mountains.

The crew entertained themselves with theatricals and lectures. Shackleton started a newspaper called the South Polar Times, which focused on the human aspect of Polar exploration. Bernacchi took over as editor in 1903.

Joe remained Bernacchi’s companion throughout the expedition. On the trip back home, however, as dog food ran short and his strength failed him, Joe had to be humanely put down. This good boy was a pioneer in many ways, being one of the dogs to pull the sled that broke the furthest south record on this second voyage.

Post-expedition, Bernacchi received several accolades. He maintained friendships with the crew, including the captain, Scott, who stood as best man at Bernacchi’s wedding in 1906. Scott invited Bernacchi to join him on his Terra Nova expedition, a return to the Antarctic, but Bernacchi declined. This decision may have saved Bernacchi’s life, as Scott and his party of five tragically died on their return trip from the South Pole. Bernacchi would remain active in scientific organisations and write several books before passing away in 1942 at the age of 65.

Now, Bernacchi is immortalised alongside Joe on the Hobart waterfront. A man and his dog, planting a flag down in history. There is a story behind every statue and this is theirs. Next time you pass by them, why not give Joe a little pat. He deserves it.