Solomon Blay: Tasmania’s Infamous Hangman

by Hobart Magazine

On execution days, prisoners were led to the gallows in shackles. The last person they saw before their demise was the hangman. A black hood was placed over their heads. All they could do was wait. As grim as this sounds, imagine the life of the hangman, who had to carry out these duties again and again.

Tasmania, with its dark history, offers many spine-tingling tales. Among these is the story of Tasmania’s infamous hangman, Solomon Blay. Born in England in 1816, Blay grew up amid severe social inequality and personal poverty. His circumstances led him into petty theft, and he was sentenced for a year for stealing potatoes and four months for stealing onions.

At this time in the United Kingdom minor crimes were judged harshly, and with gaols overflowing, the British Empire began sending convicts to Australia. Blay’s ticket to the land down under was stubbed when he was sentenced to 14 years’ transportation for attempted counterfeiting. In 1836, when he was just a young man, he was sent to Tasmania aboard the ship. In 1838, Blay was appointed as a police constable in Brighton while he was still a convict.

However, his tenure was short-lived due to his struggle with alcohol. He was then assigned to a nearby chain gang. In 1840, he saw an advertisement for the position of hangman. Seeing an opportunity to change the direction of his life, Blay applied and got the job.

The role of hangman was crucial for the British Empire but was one that few wanted. It required a unique disposition, and often those who took up the job faced madness and social ostracism. While people in higher positions of justice were well-regarded, the hangman received no such recognition, despite the significant weight of the role. Life as a hangman was a lonely and alienating one.

Blay’s first hanging was in 1941, a double execution of bushrangers John Watson and Patrick Wallace. They were hanged in Launceston for an armed robbery near Ross. Many more of Tasmania’s bushrangers fell to Solomon’s noose. As Tasmania’s primary hangman, Blay took the job seriously and gained considerable notoriety. Over his long career it is estimated that he executed 206 people, including three women. Starting at the age of 25 and continuing until he was 71, he holds the record as the longest-serving hangman in the British Empire.

While it’s easy to imagine Blay had a thirst for death, this would be an unfair judgement. It was the harsh realities of life as a convict that forced Blay to take the lives of his fellow criminals for the Empire. There was very little opportunity for a man like him, and while it led to a morbid, lonely life, it was ultimately a decision of self-preservation. We don’t even know what Blay looked like. No photos exist of him as he refused to be photographed, and he hated being recognised in public due to the scrutiny he faced. However, his convict record indicates he was of medium height, with dark brown hair and blue eyes. In 1857, he received a full pardon.

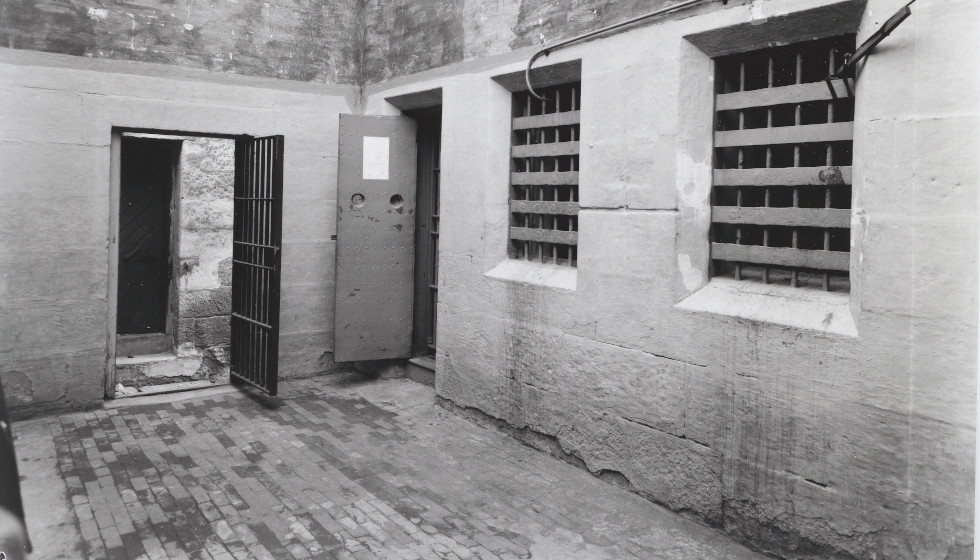

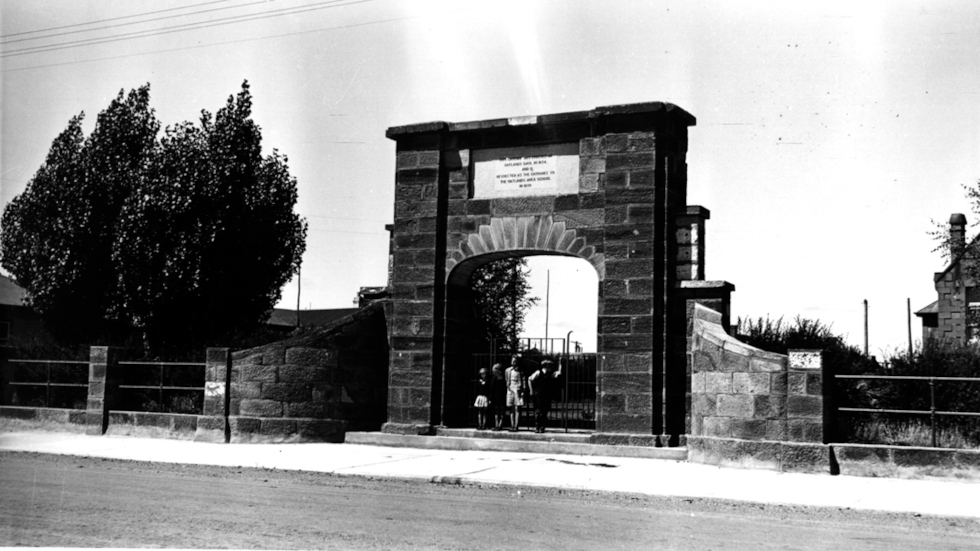

Blay lived in Oatlands and performed hangings at the local gaol, but he also travelled to the Hobart Penitentiary (where the gallows he used can still be seen) and Launceston Gaol (Launceston College now sits upon its ruins) for his work.

He often hiked the multi-day trek from Oatlands to Hobart and Launceston, as few passing coaches or travellers would offer him a ride due to his reputation, although some believe he walked to save money. Blay’s lonely hike between executions is commemorated by a bronze silhouette sculpture on the Midland Highway, south of Oatlands. It is one of 16 sculptures created by Folko Kooper that tell the history of the Midlands.

Blay was paid per hanging, and while it wasn’t a lot, the taxing job had its benefits. He was allowed to keep the clothes of the prisoners he executed, and his wife sold these clothes for extra income. And who was his wife? Mary Murphy, an Irish convict who was sent to Australia for setting fire to a house. Mary, just a few years younger than Blay, was described as having a fair complexion, dark brown hair, and hazel eyes with a noticeable squint. After arriving in Tasmania, she was briefly a housemaid, but was sent to the Cascades Female Factory for being drunk, then again for being in possession of expensive clothes. At some point she made her way to Oatlands, where she became very friendly with Blay, and they soon married. Mary was wise and she took charge of their finances.

Eventually, they saved enough to move back to England with the dream of living a quiet life in a small cottage. However, their dreams were dashed when Blay’s identity as Tasmania’s hangman was discovered there. Fearing further scrutiny, they decided to return to Tasmania, and with few options, Blay resumed his role as a hangman. They spent the rest of their lives in Hobart. Mary passed away in 1884 at the age of 60.

Blay continued his work until 1887, when he retired as a 71-year-old man. He spent his last decade in solitude, passing away in 1897 at the age of 81. He was buried in an unmarked grave at the Cornelian Bay Cemetery, while Mary rests in a marked grave nearby. Although Blay faded into obscurity at the time of his death, his name endures in Tasmanian folklore. His story is a reminder of the harsh lives of convicts who were sent here against their will. His spirit is said to haunt the Hobart Penitentiary, as well as the ghosts of those he executed.

You can take one of the Hobart Penitentiary’s tours (www.nationaltrust.org.au/places/penitentiary) to learn more about Solomon Blay’s story, or consider picking up the book Solomon’s Noose: The True Story of Her Majesty’s Hangman of Hobart by Steve Harris.

Did you know? A Celebrity Tried to Contact Solomon’s Ghost

Jack Osbourne, Ozzie Osbourne’s son, visited the Hobart Penitentiary last year to film his paranormal investigation mini-series, Buried Bloodlines. He dedicated quite a bit of time in the gallows attempting to contact Solomon Blay, and got freaked out on more than one occasion. In this show he also visits Willow Court Asylum.