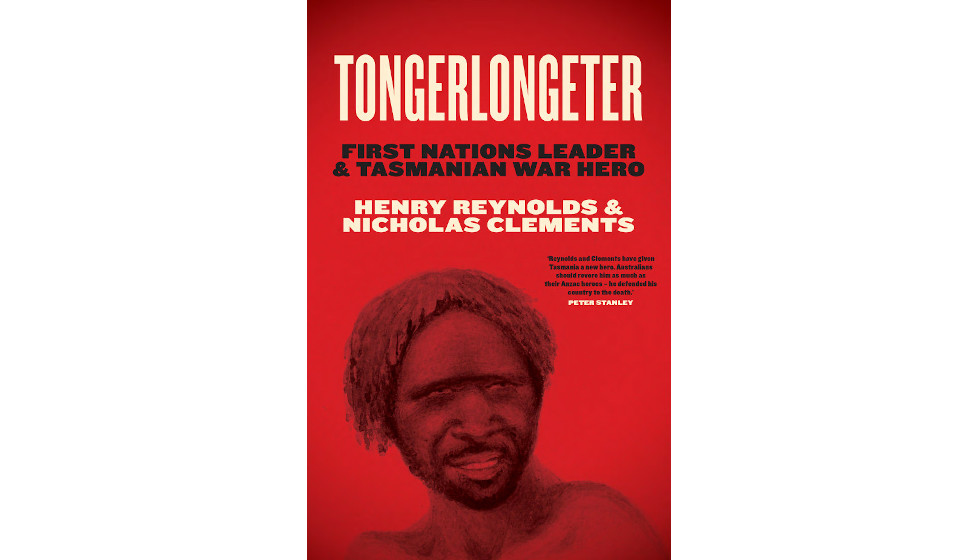

Historic Battles and Exile in Tasmania

by Nicholas Clements

Tongerlongeter was an impressive Australian war hero. Leader of the Oyster Bay nation of south-east Tasmania in the 1820s and ’30s, he and his allies led one of the most effective frontier resistance mounted on Australian soil.

Tongerlongeter’s brilliant campaign inspired terror throughout the colony, forcing Governor George Arthur to launch a massive military operation in 1830 – the infamous Black Line. Authors Henry Reynolds and Nicholoas Clements recently released book Tongerlongeter: First Nations Leader and Tasmanian War Hero, explores the life and battles of this Tasmanian leader. Here’s an extract about meeting Governor Arthur in Hobart on 7 January 1832, shipping out to Flinders Island and what this meant for Tongerlongeter and his people, but also for the colonists.

After eight gruelling years, the fighting was over. The armistice George Augustus Robinson forged with Tongerlongeter and his key ally Montpelliatta was, as 19th- century historian James Bonwick declared, ‘by far the grandest feature of the war’. The chiefs had, in Arthur’s words, led ‘the two worst Tribes which had infected the Settled Districts’, having ‘always shown themselves to be the most blood-thirsty’. Still, the governor had developed a grudging respect for this ‘crafty foe’, conceding that ‘their cunning and intelligence are remarkable’.1 And now, on this the first Saturday of the new year, he would finally get to meet them face to face. As his staff busied themselves with preparations, Arthur heard the sound of the cheering crowd grow louder and louder as the procession made its way down Elizabeth Street towards Government House.

When they came into view, Tongerlongeter, with his imposing stature and his missing arm, was unmistakable. He wore his new cloak – a symbol of the pact he had made with Robinson. Behind him was the unbeaten remnant of one of history’s most enduring peoples. Their maimed bodies and lined faces told a fearful story, and yet they stood tall, spears in hand. Arthur lavished them with hospitality, even wheeling out the military band, but it was all too much. They were there to be heard, not serenaded. The band was silenced, and the delegations moved inside.

We will never know what was said in that meeting. Would the chiefs have agreed to simply abandon their beloved country for permanent exile on an alien and inhospitable island? Such a concession, especially after Robinson’s lofty promises, seems inconceivable. All we know is that ten days later the whole party set sail for Flinders Island. Onlookers surely recognised the significance of the moment. Here were the island’s vanquished original owners, exiled from the country of their birth.

The feelings of the townspeople were conflicted. On the one hand, many were inspired by the ‘lost cause’ narrative of determined warriors defending their country against impossible odds, and very nearly to the last man; on the other hand, the removal of this stubborn enemy relieved them of an enormous burden. The fear that had filled the air for so long was finally gone, and the colony’s stultified economy was now free to grow. In the interior, shaken colonists tried to put ‘those days of terror’ behind them. The firing holes that had been hacked into the walls of every exposed hut could now be boarded up, and the guns issued to convicts repossessed. ‘A complete change took place in the island’, one settler recalled; ‘the remote stock stations were again resorted to, and guns were no longer carried between the handles of the plough’.2

The land itself bore the marks of war. The Black Line had cut a swathe through more than a million hectares of bushland, the evidence of which remained for years after. Dozens of newly and half- constructed ‘trap huts’ – Arthur’s latest plan for surprising Aboriginal war parties by hiding armed men in secluded huts – were abandoned to the wildlife. And some 258 graves, all that remained of the men, women and children killed by Aborigines, littered the landscape as a memorial to the cost of free land.3 But the greatest change to the Tasmanian landscape wasn’t the presence of any of these things; it was the absence of the people who had created that landscape.

1 Arthur to Murray, 20 November 1830, and Arthur’s memorandum, 20 November 1830, in Shaw, VDL, pp. 60, 73.

2 HC Stoney, A Residence in Tasmania, Smith, Elder & Co., London, 1856, p. 33.

3 Clements, ‘Frontier conflict’, p. 343. The totals from this 2013 compendium (which catalogues violence across Tasmania, not just in Oyster Bay – Big River territory) have since been adjusted based on subsequent discoveries and corrections that appear in Clements online compendium,