How Whale Blubber Built Sandstone Salamanca

by Zilla Gordon

If you took a stroll through Salamanca at the turn of the 19th century, you would have been greeted with the putrid smell of chunks of whale blubber, rendered down in cast-iron pots called try-pots; a far cry from the modern cocktail scene today.

But it was those gruesome sights that shaped the city – because Hobart was built on a whale’s back. While Hobart’s whaling history may go back to the time of the first European settlement, it was around the 1840s to 1880s that the industry entered what historians say was a golden age. And a warning, gruesome tales ahead.

WHALES TURN TIMID

Whales were once abundant in Hobart’s estuaries, in fact, clergyman and avid dairy-keeper, Robert Knopwood said in 1804 that the animals were a hazard. “We passed so many whales that it was dangerous for the boat to go up the river unless you kept very near the shore,” he said.

Because whale oil was used to light Hobart’s streets and homes, the demand for the animals continued to increase. “At that point, the owners of the whale stations thought the whales were getting ‘shy’,” historian and researcher Michael Stoddart said. “In fact, what they meant was they’d butchered all the whales that came close to the shore, and the whales were all too far out to sea to make this shore-based station hunting work.”

The golden age transformed the waterfront and masses of whaling ships were built, designed and moored in Hobart. “There were shipyards all over the place building these ships,” Michael said. Hobart created such a name for itself, ships from America were lining up for a mooring. The abundance of whale oil even drew British and Portuguese ships to Hobart, and these ships meant money. “In 1838 it’s said that more money came into the state treasury from whaling than from any other primary industry,” Michael said. “All the agricultural exports, put them all together, and they didn’t equal the amount of money that came in from the sale of whale oil.” And all that money allowed for the constructions of some of Hobart’s finest buildings.

A CITY OF GRANDEUR

The Lenna of Hobart Hotel was owned by the successful whaling family the McGregors. “At the top of the old house, there’s a lookout – a clerestory – that he built so he could walk up and look at his ships coming up the estuary,” Michael said. “He’d go up there with his binoculars or his telescope and he’d wait for his ships to reappear. You’d say goodbye to your ship and in a year-and-a-half, you might see it again.”

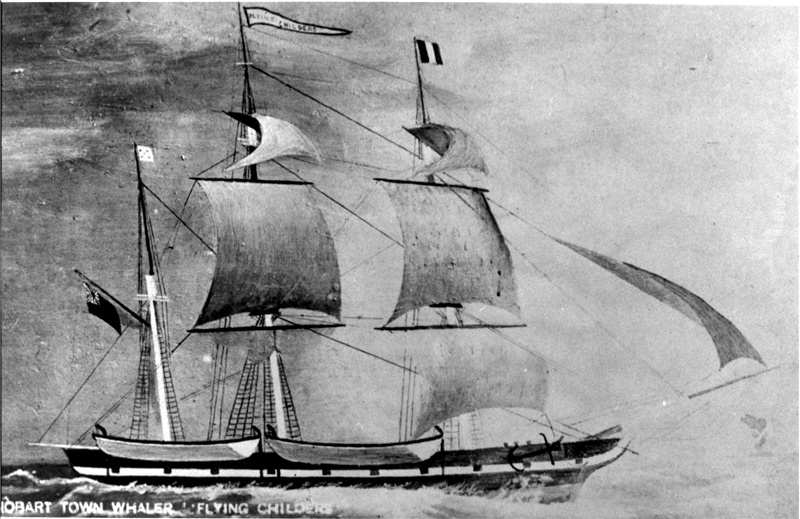

Patriarch Alexander McGregor owned the prized whaling ship The Flying Childers, named after a Launceston racehorse, which made nearly 40 trips in its lifetime and sometimes spent up to a year-and-a-half out at sea. “It never came back without its hull being full of oil,” Michael said.”

A HARD DAY’S WORK

Rather than a restaurant, Maldini was originally an iron foundry, and the stretch of sandstone buildings housed blacksmiths and ropemakers. And perhaps more importantly, there were lots of pubs. “The crew left the ships like rats from a sinking ship and just headed for the pubs,” Michael said. They frequented an area around a wharf at Hunter Street, known as Wapping: which also offered brothels, drinking halls and boarding houses – and boasted a rough reputation.

But the on-shore frivolities were a stark contrast to their back-breaking work. The golden age was really quite miserable. “A great many men were killed leaving orphaned children,” Michael said. On the water, whalers would pursue the animal in small wooden boats which were often damaged during the chase. “A lot of whales would smash them with their tails,” Michael said. “They’d be six boats out, maybe chasing one whale – they’d be rowing for an hour.”

Killing the whale was only half the battle with the animal then dragged back to the ship. “It could be eight hours of doing nothing but rowing your boat,” Michael said. “And there might have been a chunk taken out of the side of the boat, so not only were they rowing, but they were also bailing like mad to stop them from sinking.” The deceased whale would be tied up alongside the ship, and mounds of blubber would be hauled up by a pulley and dropped into the try-pot and the oil then rendered, all while out at sea. The rest of the whale would be cut adrift.

END OF AN ERA

By the end of the 1890s, things had changed. Whales were very difficult to catch, even for ships that had headed far out to sea. “That was it, Hobart’s whaling industry was over,” Michael said. So whaling ships were converted to cargo ships and instead carried Tasmania’s apples across to the mainland. Whaling returned briefly in the 20th century when Norwegian ships used Hobart as a base to head further south to Antarctica to hunt for blue whales from around the 1920s to the 1930s. The ships’ arrival offered jobs for around 200 men and there were records of boys as young as 16 years old being employed. “One lied about his age because they wouldn’t take them as young as 16,” Michael said. “But the majority of them were in their very early 20s. These young men went off for the adventure of a lifetime, not really knowing that they were being involved in the destruction of the Earth’s stocks of blue whales.”

So successful was the Norwegian whaling industry that by the Second World War “there was hardly a blue whale to be had”, according to Michael. “Maybe there’s about one-tenth of the blue whales left in the world that there was in the 1920s when the young Tasmanian boys went south. “But the fact was, the world needed whale oil, and it was their job to deliver it.”

Today remnants of whaling’s golden age can still be found in Salamanca’s buildings, Michael said. “Look up and you’ll see some of them have still got pulleys… so that platforms could be raised and lowered, and barrels of oil stored in the buildings.”